On a sunny morning, our group of FairFrontiers members moved from Hasanuddin University’s education forest in Bengo Bengo Hamlet to the photovoice exhibition site in Jambua located in Limapocoe Village, Cenrana District, Maros Regency, South Sulawesi. The distance between the two locations is only about 10 minutes by car, but on that day, it took us nearly an hour. The narrow road leading to the nearest accessible point is only wide enough for one car, and the limited parking space could accommodate no more than two cars at a time, making it necessary to wait for our turn to be picked up and shuttled to the site.

From the parking area, we walk along a small, uneven road surrounded by rice and bean fields, a river, and forestland. Navigating this road by motorcycle would require at least an average level of skill, as its condition was far from smooth. As I made my way, I couldn’t help but think of the villagers who must have worked tirelessly to carry the exhibition materials through this challenging terrain. It was no easy feat, but their efforts reflected a deep commitment to ensuring their voices were heard. Despite the physical difficulties, they persisted, determined to tell their story through the photovoice exhibition.

We were greeted by dozens of photographs, each capturing heartfelt stories from the villagers. Nearby stood a tent, roughly 8 by 15 meters, supported by newly harvested bamboo, it is fresh appearance revealing that it had just been sourced from the surrounding forest. The simplicity and rawness of the structure reflected the community’s deep connection to their environment.

“We offered this location to the organizer, and together with the residents, we built this simple tent to welcome the guests invited to hear our voices through these photos,” explained the hamlet head. His words underscored the community’s collaborative spirit, their collective effort to create a space where their stories—told through the lens of the photovoice exhibition—could be shared with the world.

Photovoice Exhibition: The land and its people

The photovoice activities were led by researchers from the Forest and Society Research Group (FSRG) at UNHAS, who empowered the local participants to capture their changing landscapes. Armed with their phone cameras, the local people set out to document their everyday realities and the struggles they face. The photos they captured were later showcased in an exhibition. Our interaction with the photovoice participants when discussing the photos taken allowed us to dig deeper into their stories and aspirations. At this very moment, the local people themselves decided whom they wanted to invite to hear their stories. This exhibition features photographs from Limapoccoe and Rompegading villages in South Sulawesi and Tamalea village in Mamuju, West Sulawesi. Almost half of Limapocoe Village is forested, with around 70% of the area being protected forest and the rest limited production forest. Rompegading village is in a similar situation, with more than half of its area being protected forest. The UNHAS education forest also covers a small part of the area in both villages. Meanwhile, Tamalea is a village with the same problem as the two mentioned villages—having complex issues. Besides the indigenous population, there are also transmigrants (part of the government’s transmigrasi program). More recently, a private company has started its operations for coal mining. Through photovoice, the young people in Tamales learned how the transmigration program and the extractive industry, such as coal mining, led to landscape change and impact ecosystem services in their village.

All of the local communities from the location see the land as not just a resource—it is the foundation of their identity, heritage, and livelihood. For generations, the people here have relied on farming, harvesting natural resources, and living harmoniously with the environment.

“I’ve been waiting for this day, hoping they would finally listen to us,” shared one resident moments before the exhibition officially opened. “We were never considered here. They came without warning, marked the forest boundaries, and declared it theirs. No notice, no discussion, and no solution was offered when our land suddenly became part of the forest area”.

The exhibition location was dominated by local people and stakeholders in the area, and the problems discussed were more centered on Limapocoe and Rompegading villages. In recent years, villagers faced growing challenges to reclaim their land rights, which are increasingly being squeezed and shrunk due to national policies that mostly purport to preserve nature, protecting animals such as the endangered monkey. “How important is the existence of monkeys that our existence is not taken into account?” said the Hamlet head when allowed to speak before guests at the opening of the Photovoice exhibition.

This Photovoice exhibition was held alongside the FairFrontiers Project Annual Meeting and allowed FairFrontiers members to witness firsthand the power of this initiative. Over twenty evocative photographs were displayed, each set in distinctive, rustic wooden frames that complemented the village’s natural surroundings. These images vividly depicted the challenges faced by the community, offering an intimate look into their deep connection with the land and the impact of the imposed forest regulations. While every photograph had received full consent from its owner to be displayed, the names of the photographers were intentionally omitted for security reasons, reflecting the sensitivity of the issues raised.

Stories of fear, intimidation, and the struggle amid changing land boundaries

Local people are grappling with fear and intimidation as their ancestral lands are increasingly encroached upon by expanding forest boundaries and mining activities. Villagers face the constant threat of displacement as government policies and corporate interests reshape the landscape, often without consultation or consent. The protected forest designations and mining operations have squeezed local livelihoods, leaving residents feeling powerless in the face of land grabs.

Their stories are revealed through the photos they capture. Most reveal the helplessness, fear, and threats they experience when trying to reclaim their land rights. The trees they planted for their children’s and grandchildren’s inheritance cannot be cut down, they have lost access to the forests that have supported their lives, the land they used to grow crops is now small and some can no longer be used at all as a result of land changes. Although people recognize that change is certain, they still expect that they want to be involved in any plans for changes related to the land they use.

Several key themes emerged from the photovoice exhibition. First, there was the heartbreaking loss of ancestral lands, as villagers shared stories of being displaced from land passed down for generations. Many feared that future generations would not only lose their homes but also their cultural heritage. Another pressing theme was the environmental impact, with participants highlighting the degradation of forests, rivers, and farmland due to mining company activities. This destruction has directly impacted the village’s food production and access to clean water. However, amidst the struggles, a sense of resilience and hope also radiated throughout the exhibition. The villagers expressed their determination to protect their land and reclaim their rights, united by a shared belief that their collective voice could bring about meaningful change.

a) Lost twice: We had a bad experience of losing land in the 1990s. When the Bosowa Corp mining and portland cement plant in Bantimurung District was about to operate, my parents were intimidated and forced to sell their lands to the company. Such experience reoccurred here when the forest authority planted forest stakes on our land and determined them as forest areas. But it is quite strange this time. There was no any compensation and solution. We were just told to obey the rules and even threatened to be prisoned.”

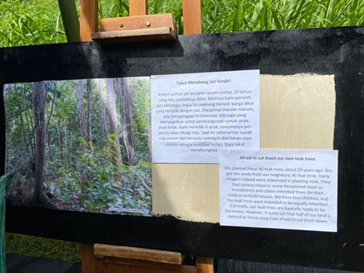

b) Afraid to cut down our own teak trees: We planted these 40 teal trees about 20 years ago. We got the seeds from our neighbors. At that time, many villagers indeed were interested in planting teak. They had various reasons: some threatened them as investments, and others inherited them for their children to build houses. We have four children, and the teak trees were intended to be equally inherited. Currently, our teak trees are basically ready to be harvested. However, it turns out that half of our land is claimed as forest area. I am afraid to cut them down.

The exhibition as a platform for advocacy

One of the most powerful aspects of the exhibition is the personal narratives that accompany the photographs. At first glance, the exhibition looks like an art exhibition, but the stories make the exhibition a platform for advocacy for change. It’s encouraging people to take action, whether that’s raising awareness, supporting a cause, or getting involved in social issues. The combination of art and personal storytelling turns the exhibition into a call for empathy and action. These stories make the exhibition a powerful platform for raising awareness about important social issues. By sharing individual experiences, the exhibition helps people to connect emotionally to the subjects and understand the challenges they face. This emotional connection is what makes photovoice and its exhibition, a compelling decolonization research method. By encouraging the local community to participate as conscious subjects who choose what kind of picture and history they are willing to share with the world, photovoice empowers participants. In this way, it not only amplifies grassroots voices but also advocates their interests, transforming research into a collaborative and inclusive process.

Looking ahead to the future

The Photovoice exhibition in Jambua had a profound impact on both the participants and the community. For the villagers, it was an empowering experience—giving them confidence in their ability to advocate for their rights. Many participants expressed that the process of documenting their experiences helped them see their struggles in a new light and strengthened their resolve to fight for justice.

For the broader audience, the exhibition served as an eye-opener. Government officials and other relevant stakeholders who attended the event listened to the local people’s stories and promised to convey what they heard to higher authorities. At the fair, it appeared that only the dean of the forestry faculty was committed to further dialogue regarding UNHAS’s Education Forest. Importantly, the exhibition inspired other communities in South Sulawesi and beyond to consider using Photovoice as a tool for raising unheard voices.

The narratives from all the photo discussions are being analyzed using qualitative text analysis techniques. So far, only the village of Tamalea has been fully coded and analyzed. This analysis is being carried out by multiple researchers, not just from FSRG but also from FairFrontiers at RIHN. However, the diversity of perspectives among researchers from different disciplinary backgrounds also presents a challenge, as differing interpretations of local narratives can also lead to debates and disagreements in the analysis. A key lesson is for all of us to keep an open mind and to learn to read the narratives as deeply grounded indigenous, and not as scientific, epistemologies.

Written by Andi Patiware Metaragakusuma, Kasmiati and Pamula Mita Andary